Fiona Pardington | 100% Unicorn

24.05.16 - 25.06.16

24 May – 25 June 2016

‘Well, now that we have seen each other,’ said the unicorn,

‘if you’ll believe in me, I’ll believe in you.’

–Through the Looking Glass, Lewis Carroll, 1871

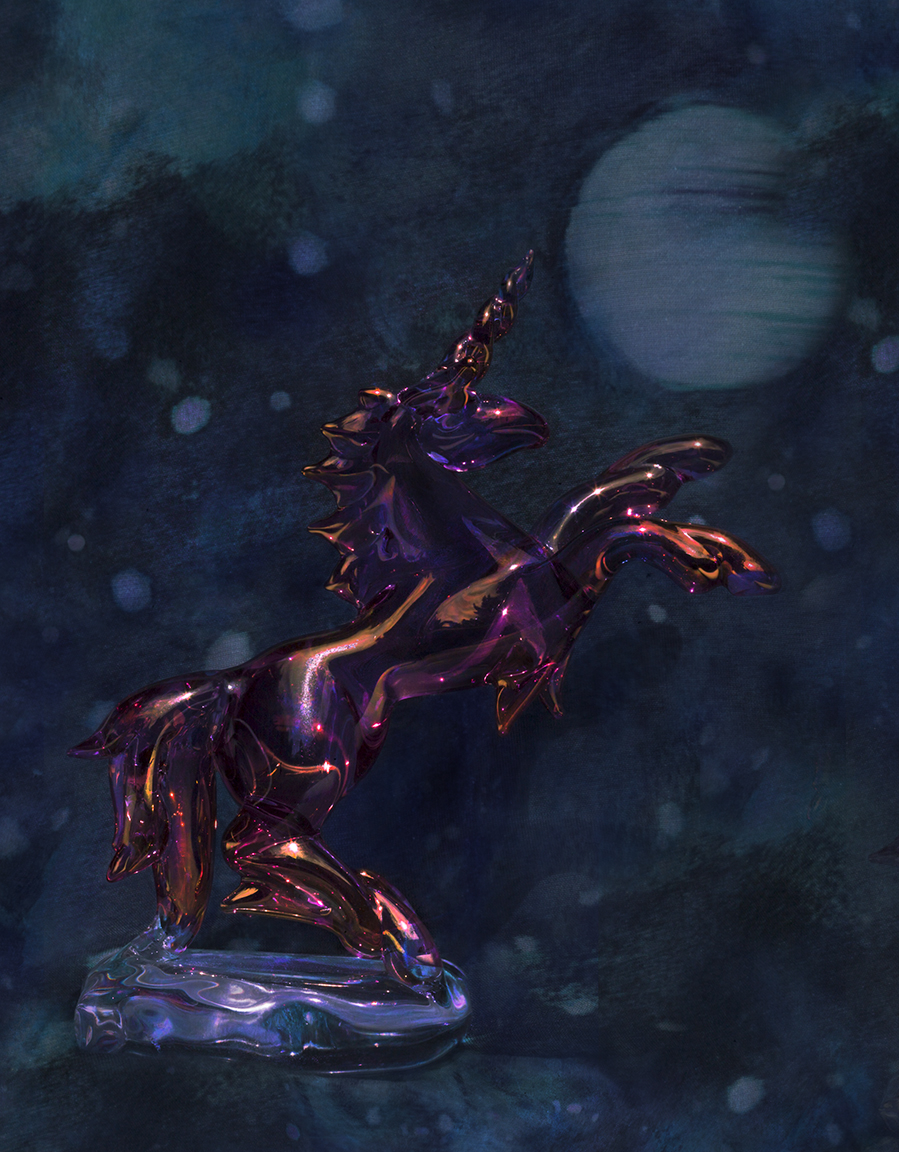

Fiona Pardington’s menagerie of glass unicorns perform several functions in the context of the still life. Traditionally glass objects frequently appeared in vanitas paintings, symbolising the fragile ephemerality of life, but also allowing the artist to show off their skill in depicting its translucence and reflective qualities. In Pardington’s work they also allude to the photographic process, manipulating and directing light. When the Abbot Suger (ca 1081-1151) set about in 1137 renovating the Church of Saint-Denis in Paris, in the Rayonnant Gothic style, stained glass was central to his vision, likening the light passing through the glass as being like the Holy Spirit illuminating the soul without changing its substance. Light plays a similar transformative and spiritual role in Pardington’s work. Light is what unifies the compositions visually and metaphorically.

The Unicorn is an ancient and archetypal beast. The version we mostly think of is the stallion with a single horn thrusting from its brow, rearing rampant, as seen in the famous Flemish tapestries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Cloisters Collection in New York, and as the heraldic lunar beast of Scotland (mortal enemy, now co-shield bearer of England’s solar lion) in the coat of arms of the United Kingdom. Most often the mythological cryptid represents a paradoxical mix of meanings: lust, purity, virility and the masculine principle, chastity, chivalry, loyalty, ferocity, the divine right of kings, all manner of virtues, fantasy, and magic. Its spiralling, phallic horn was reputed to purify water, and it was said that it could only be tamed by a virgin. As Leonardo da Vinci wrote in his notebooks: “The unicorn, through its intemperance and not knowing how to control itself, for the love it bears to fair maidens forgets its ferocity and wildness; and laying aside all fear it will go up to a seated damsel and go to sleep in her lap, and thus the hunters take it.”

Although in recent years the unicorn has been manifest in the sublimity of Peter S. Beagle’s 1968 novel and subsequent 1982 animated film The Last Unicorn, and the playful ridiculousness of Lauren Faust’s reboot of the My Little Pony franchise, the unicorn is as old as civilisation itself. The Indian Museum in Kolkata preserves depictions of it on seals from the Indus Valley civilization dating back to 2500BCE. For the Greeks, it was an actual rather than mythological animal. Ctesius of Cnidus (fifth century BCE) describes the unicorn as a kind of wild ass native to India. The earliest references to the unicorn-like qilin can be found in Chinese writings around the same time. Strabo (64BCE-ca 24CE) in his Geographica places them in the Caucuses. Pliny the Elder (23CE-79CE) writes of it in his encyclopaedic Naturalis Historia, calling it the Monoceros. Aelian (ca 175-ca 235CE) writes that the Monoceros was also called the Cartazonos – which some scholars suggest is related to the word Kargadan which is both Persian and Arabic for Rhinoceros. Marco Polo was clearly looking at a rhino when he wrote of the unicorn, “They are very ugly brutes to look at. They are not at all such as we describe them when we relate that they let themselves be captured by virgins, but clean contrary to our notions.”

The unicorn as we think of it today, however, the unicorn of these little glass and ceramic figurines, is a product of medieval Europe. The early bestiaries made the story about virgins and unicorns an allegory of Incarnation of Christ. For later poets like Thibaut of Champagne (1201-1253, King of Navarre from 1234), Richard de Fournival (1201-ca 1260) and Petrarch (1304-1374) the unicorn was a symbol of courtly love. A brisk trade in cups of “unicorn horn” or alicorn abounded. Such vessels, usually narwhal tusk or ivory, were supposed to detect or even neutralise the assassin’s poisons. Even as late as the mid eighteenth century one could purchase powdered unicorn horn, though physician philosophers such as the Dane Olaus Wormius (1588-1654), the Englishman Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682), and the German Paul Ludwig Sachs in his 1676 book the Monocerologia had discerned and mocked the fraud in the previous century. At its height, the horn was worth 10 times its weight in gold.

The eventual acceptance that the unicorn wasn’t a real animal did not, however, deter its popularity as a symbol for the spiritual. Just as the medieval Christians saw the unicorn as a symbol of Christ, so too did twentieth century occultism see it as a symbol of the spiritual existence of humanity. The single horn on the beast’s brow came to be considered an allusion to the pineal gland – the so called “third eye” – the part of the brain supposedly concerned with spiritual and psychic matters. The horn could also be read as a ray of divine cosmic energy and spiritual revelation piercing the mundane physical world. The apparent paradox of a pure and feminine-seeming creature representing virginity defined by its masculine phallic horn could be read as an alchemical marriage of opposites that transcends sexuality – a spiritual evolution from there merely biological and procreative to the holistic sexual oneness of a higher being. The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn – the very private occult society that did much to formalise the occult revival of ceremonial magic – gave initiates the title Monocris de Astris – “Unicorn from the Stars”. While the Golden Dawn claimed to reject the sexual element of occultism, sex magician and self-proclaimed “wickedest man in the world” Aleister Crowley was an initiate before splitting off to form his own Order of the Silver Star.

It is this apotropaic reputation of the unicorn, the warding off of evil and danger that transfers to these figurines. All miniatures encourage us to project an illusion of order and control over our lives of happenstance in a chaotic and arbitrary universe, but the unicorns themselves are also subconscious lucky charms, amulets, allusions to a fantastical and magical realm beyond mundane existence. Tennessee Williams in his 1944 play The Glass Menagerie makes much of this symbolism. The character Laura Wingfield, painfully shy and afflicted with a limp from a childhood bout of Polio, uses her collection of glass animals as a way of retreating from the world. Their fragility reflects her own; quaint, slightly old fashioned, catching the light if you look in the right way. In particular Laura identifies with a glass unicorn, the otherness repressing her represented by the unicorn’s horn that distinguishes it from other animals.

Perhaps that’s why an air of melancholy attends these figurines. Their kitsch value places them outside of the continuum of artistic received taste and high culture. Kitsch, though, has its own integrity. It embraces sentimentality, which is as much a genuine human emotional response as any noble or heroic gesture. The unicorn is the ultimate symbol of the enchantment that Max Weber claimed had been driven from the world by modernity. The unicorn figurine is the transcendental made domestic and human. If it represents anything in Pardington’s art, it is the idea of Deleuzian Immanence – that all redundancies, rejections, cruelties, everything that seems outside of life, and even death itself, are all firmly embedded in life, the here and now, and the unicorn’s raised horn is a lightning conductor channelling possibility into the humblest context, bringing being and existential authenticity into the photographic medium.

ANDREW PAUL WOOD