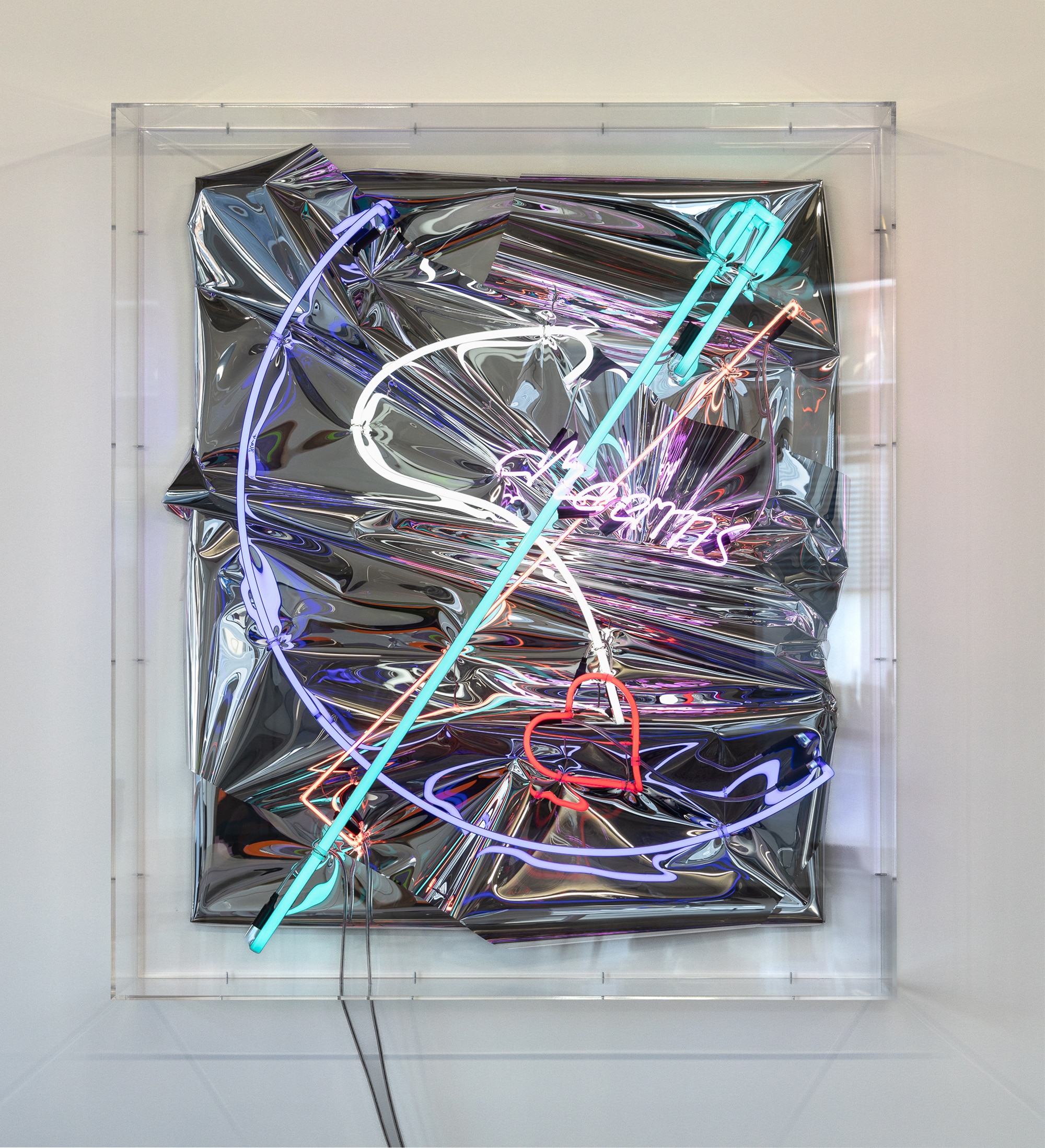

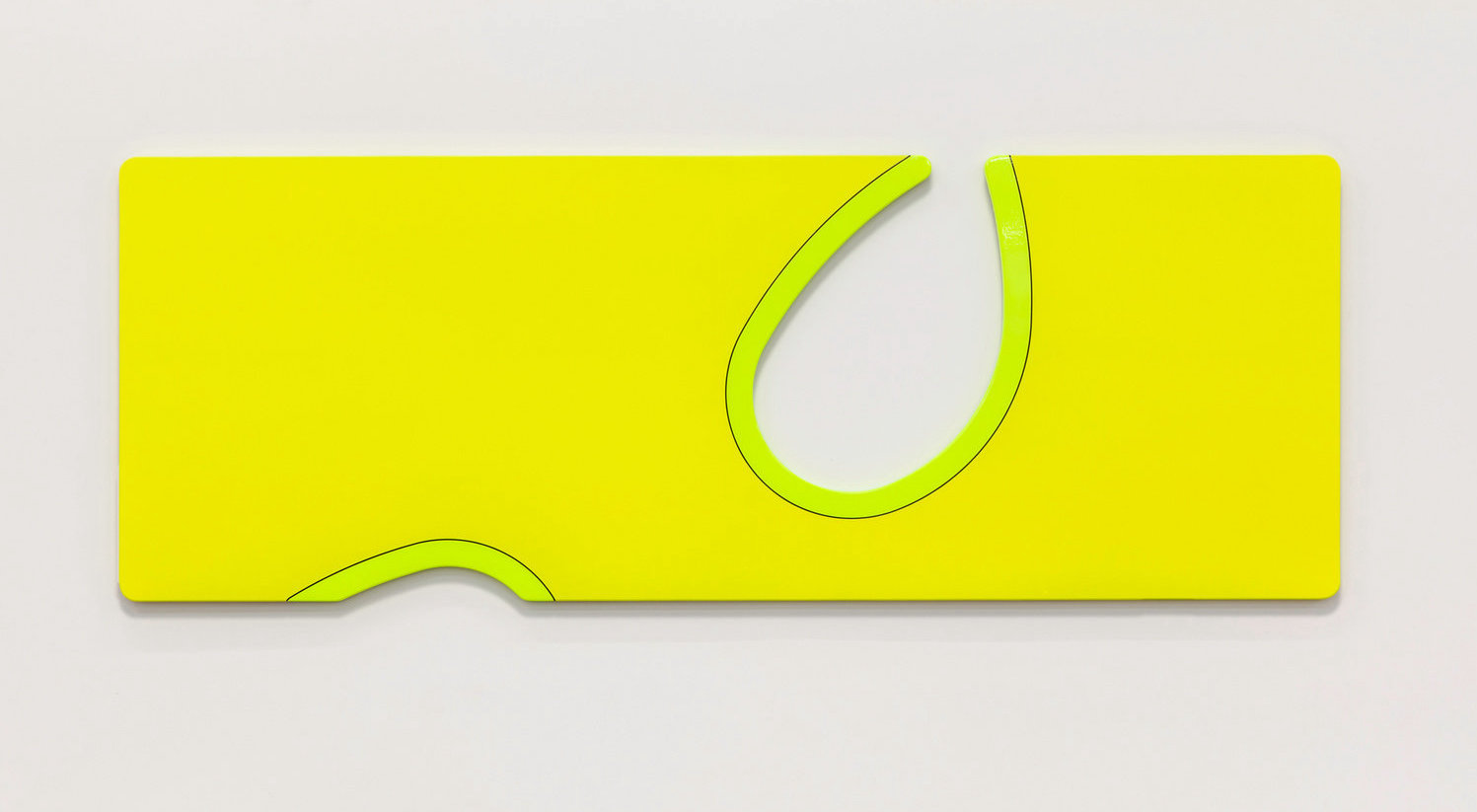

Curated by Jonny Niesche | Ümwelt

01.09.23 - 07.10.23

Daniel Boccato

Greg Bogin

Brenden van Hek

Florian Maier-Aichen

Gerold Miller

Robert Moreland

Elizabeth Pulie

Anselm Reyle

Jim Roche

Rosie Rose

Tariku Shiferaw

Jessica Stockholder

Vincent Szarek

Blair Thurman

No world but the world!

I am remembering the biologist Jakob von Uexkhüll who wrote a century ago and who I read a decade ago – my memory is vague:

A tick’s tiny world comprises its body, the upward effort of scaling grass, signs inscribed by secret vapours, the blood that is its food; a hot meal, sex, death.

Or: a child’s hand might grab the moon as if it were a nearby object. This, for the biologist, is proof that the moon is something different for a child whose sensory world is distorted, whose knowledge has not yet relegated the moon to a place unthinkably far from outstretched fingers. This local world – for a child, grownup, tick, spittlebug – is what von Uexkhüll called a living organism’s umwelt.

Every living thing is a subject who creates their umwelt through their situated perception; in this sense, every living thing is active in the production of their own environment, which is in turn productive of their very subjecthood and modes of perceiving. The biologist used the figure of the bubble to make his point, and to stress what by now seems an impossible claim: these worlds are closed and cannot be known to others.

(This memory sits somewhere in a mental archive alongside a series of black and white diagrams of an oyster’s ‘vision’, a hazy set of pixels representing the illuminatory gaze of some creaturely perception, like crude and briny headlights. These illustrations are the dream of a man who would insist that the oyster’s world is unknowable yet would nonetheless fantasise about oyster-perception’s forms of knowing and world-making.)

So many are taken by the biologist, who, a hundred years ago, predicted the preoccupations of today, a moment in which non-human being is a prevalent if endlessly complicated subject of analysis. To imagine the phenomenology of the rat is, I can admit, a kind of pleasure that is hard to refuse. But of the many who are in love with the biologist’s umwelt, few point out that for von Uexkhüll, the separation of worlds was a way of essentialising difference and therefore, implicitly or explicitly, of turning race into a signifier for ‘naturally’ separate worlds.

The word existed as a common noun in German (meaning environment, more or less) before the biologist’s propositions, which were at once anticipatory, even prophetic, as well as shamefully of his time – a time in which fascism found its home in so many metaphors of home, world, and nature. And it has come to mean other things since. Like so many things, the word umwelt contains nothing less than the history of the twentieth century.

Jacques Lacan uses the word in his theory of the mirror stage. Let’s take our symbolic child from above and ask them to consider, rather than the moon, their own reflection. The child – still a baby – confronts an image that is both of and not them. This attunement of self in world – self and world, self against world, and so on – is an attunement of innenwelt, or inner world, and umwelt, the out-there, the milieu. A biological metaphor becomes a psychological stage; a threshold through which one passes irreversibly into human subjectivity aware of itself as such. This world, painfully, is not an oyster’s.

What is our word for a world? A world inside the world, a world that indexes the historical contingency of that world – this world – yet is also a world unto itself? What is the word for a world opened by desire, or solidarity; a word for the world of an artist in the moment they perceive the material conditions of their making, in the moment the work of art emerges as a complex that contains and exceeds their imprint; a word for the world of friendship or insurrection? What is the word for “no world but the world”, as the poet Anne Boyer puts it, that is, no world but (or no worlds without) the one that is shared? We need many words for such worlds, no doubt, just as we need a ritual for the process through which we recognise and refuse the metaphors we can no longer live by. We need, that is, to burst the biologist’s bubble.

This morning, on the walk between home and preschool, the world drawn by a one-metre-tall child: perennial basil, newly blooming camellia flowers, ibis feathers, a steady descent into what was once a gully, now a bumpy shroud of broken concrete slabs, wet and insect-rich, porous as the promise of absolute difference. No world but the world, as her noticing never fails to attest.