Billy Apple, Whitney Bedford, Petra Cortright, Bill Henson, Fiona Pardington, Layla Rudneva-McKay, Yuk King Tan and Jessica Winchcombe | Recollections May Vary

08.03.22 - 29.04.22

Recollections May Vary is a group exhibition that examines representations of landscape from awry. The exhibition pokes at the idea of ‘landscape’ and presents a range of contemporary art practice that sees artists take a unique, uneasy, or individual slant on this art historical genre. ‘Recollections May Vary’ is a quote from the Queen reflecting on the Royal Family’s Megxit drama, a phrase reminding us that how we see and remember something or some-place depends on the baggage, experience, and perspective we bring to it. This is a landscape show, but not as you know it, reflective of the landscape around us and the impact it has had on our culture and collective imagination.

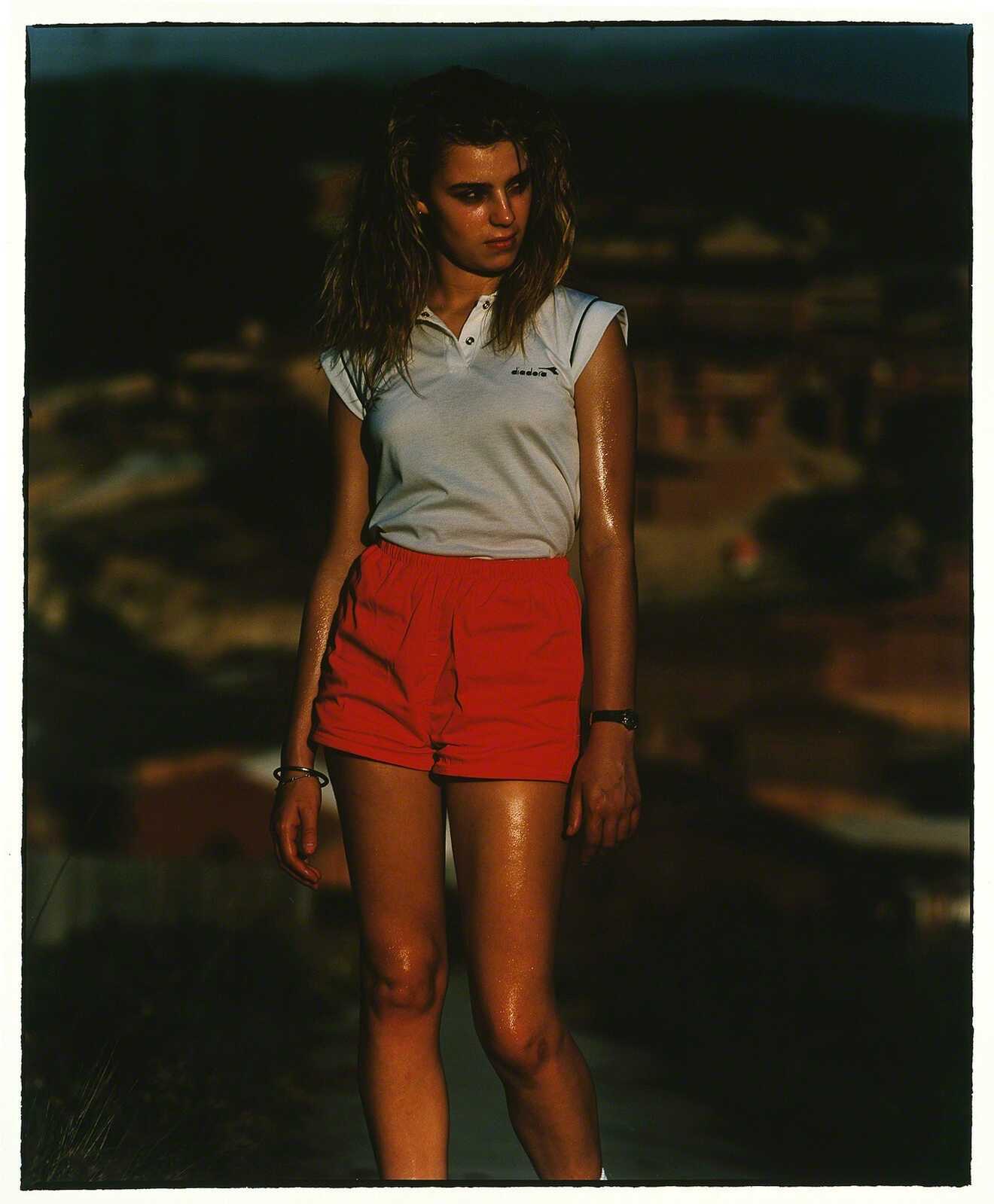

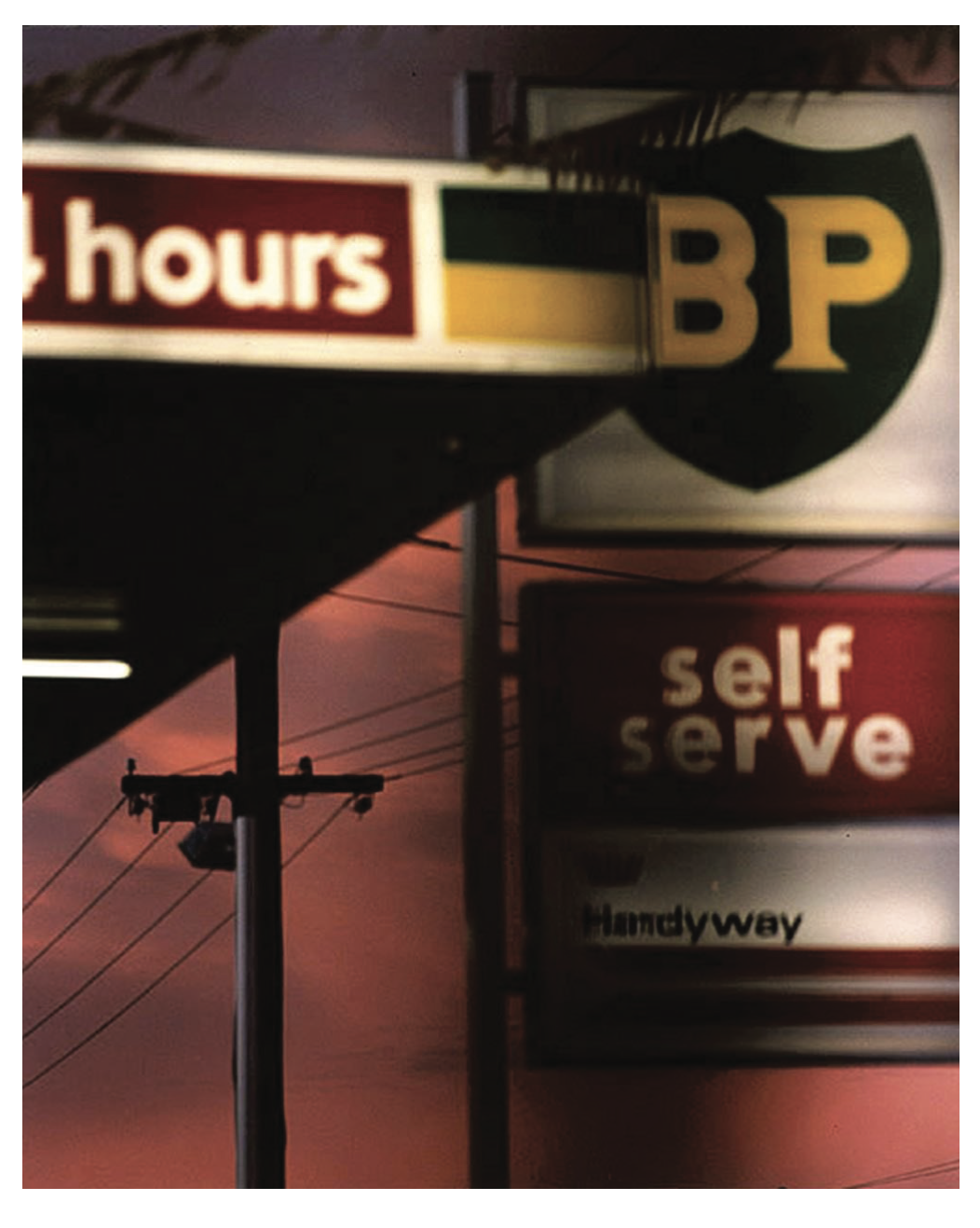

The exhibition presents a body of work by celebrated Australian photographer Bill Henson. Known for haunting, dramatic photography, Henson captures place in an in-between state that recalls cinema and dreamscape. His night-time urban landscapes are moody explorations of the twilight zones of our lives – those borders states between night and day, male and female, youth and adulthood, urban and rural. These shadowy realms that lie somewhere between the banal and magical define Henson’s practice. The narrative of his photography is evasive, back stories are alluded to but never fully told, figures appear falling or perhaps hovering, and states of emotion just begin to flicker across or disappear from faces.

Bill Henson is joined in the gallery by seven other artists whose work offers a similar take, emphasising that landscapes are culture before they are nature. Based in Hong Kong since 2005, Yuk King Tan recalls the region’s mythology to create a sculpture titled Nine Mountains. A transliteration of the Chinese 九⿓, or ‘Nine Dragons’, Kowloon is named for the eight mountains of the territory, and one symbol of a mountain dragon. Legend tells that the 9 year old Emperor Bing, the 18th and last emperor of the Song dynasty noticed the mountains and named them ‘Eight Dragons’, but a courtier pointed out that the emperor was a dragon himself, making it nine. Created from ethereal white tassel over board, the geometric shapes form cubist mountains against the gallery wall. Referencing leadership, mythology, and the mist and mountain paintings of Chinese landscape tradition, the sculptures become repositories of history and metaphors for control and failure.

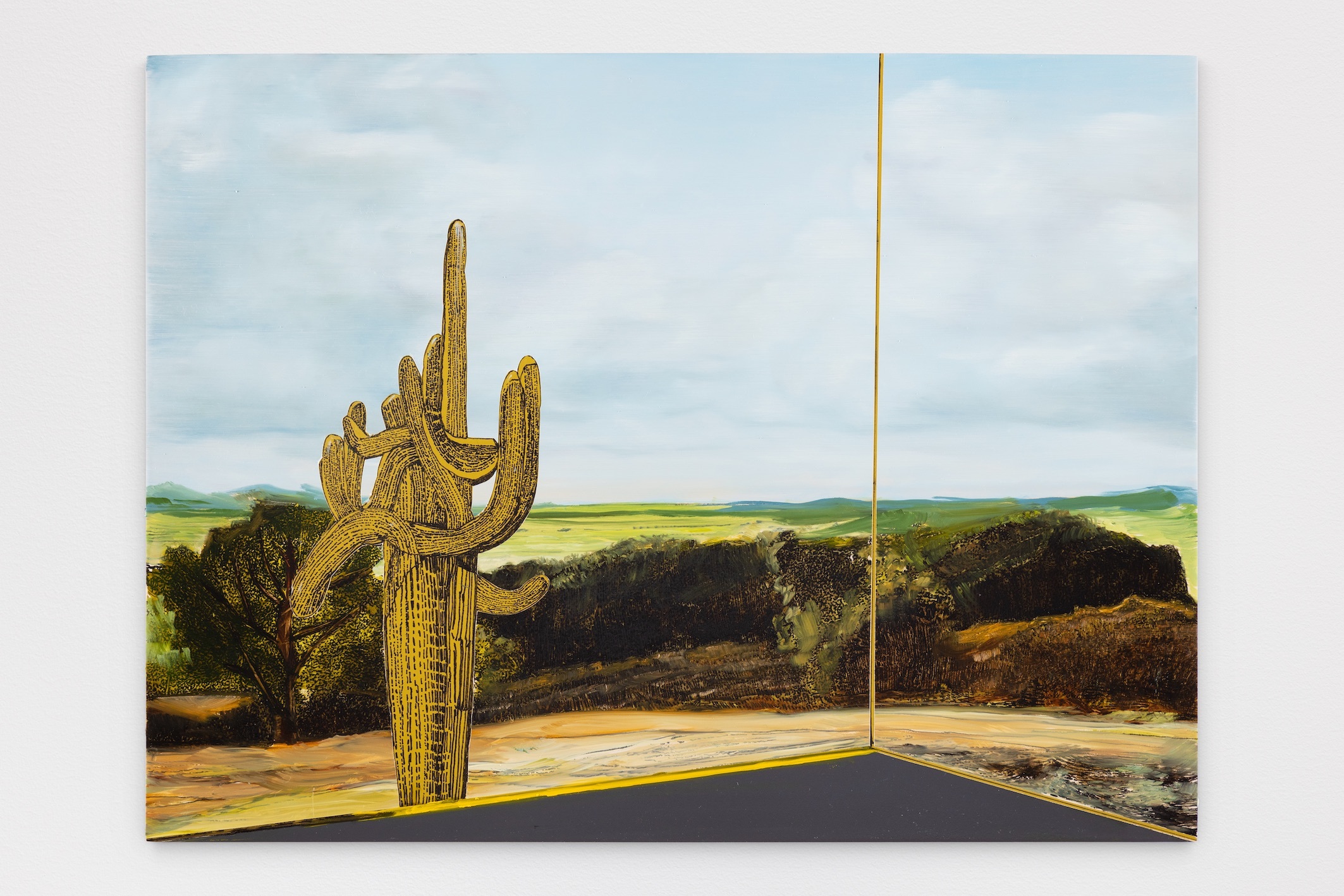

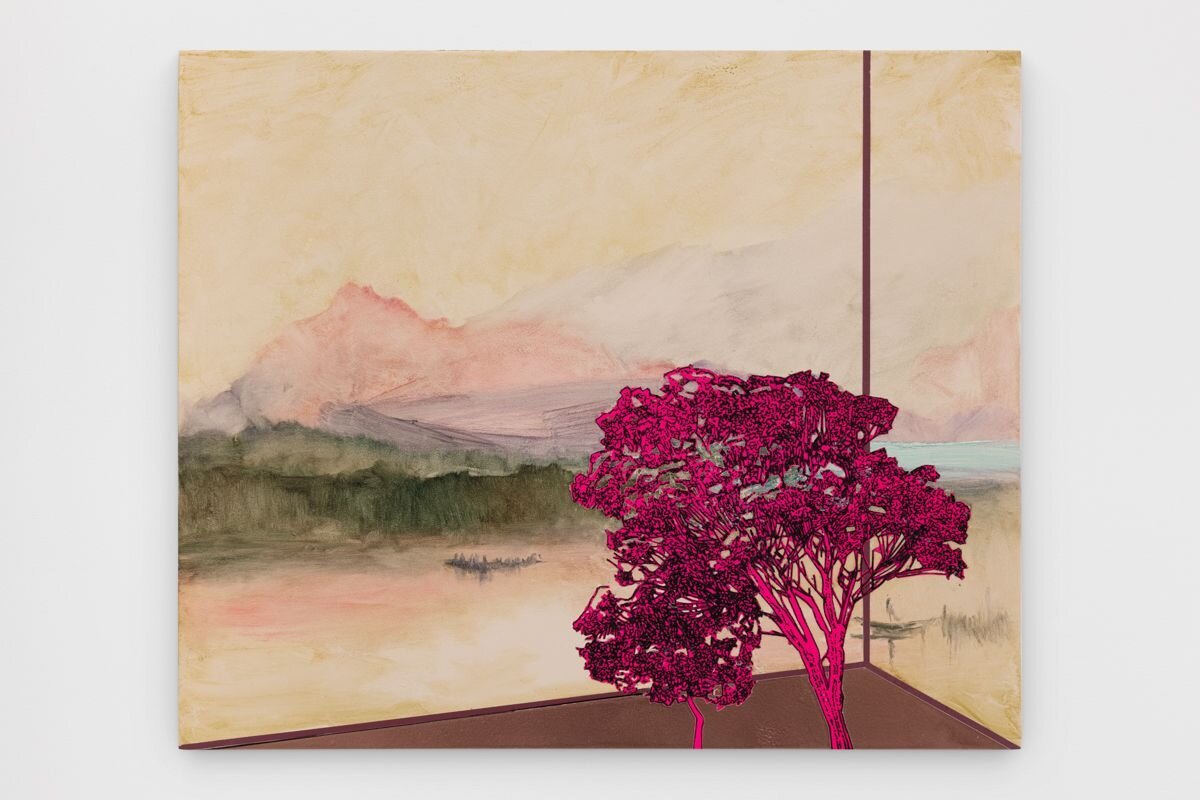

Reflecting upon how humans have chosen to record images of the natural world, Whitney Bedford’s new landscapes draw upon an archive of historical landscape paintings to illustrate how images from the past underscore the dire reality of climate change and shifting ecosystems in the present. Billy Apple’s, Study for a New Zealand Flag III, is a measure of cultural landscape or human geography. Using Statistics New Zealand’s 2018 census population data of 16.5% Māori/ 83.5% Other, the composition of Apple’s flag is determined by the representation of Māori/other population data using the proportions of the golden ratio in tones of 100% black. An interesting gauge of Māori population against the overall population, also taking into account NZ’s net immigration as a significant driver, the conceptual art work is the third in a series which began in 2009 using 2006 census population data of 14% Maori. This first art work was the catalyst for an unlikely collaboration and friendship between Billy Apple and the artist and activist Tame Iti which continued over several exhibitions.

The subject of Fiona Pardington’s photograph is a mushroom, one of a series from the mycological collection donated in 1863 to the old Museum of Natural History in Nice. Understandably, a culinary culture such as France is fascinated by fungi, and the properties and mythology of these mysterious forms runs throughout their literary and popular culture. Emerging from darkness in an echo of how fungi seemingly erupt from the ground overnight, these strange specimens spill over the picture plane, their almost mythical unreality enhanced by their fragile beauty and unknown qualities. Accompanied by a small hand written card, the key is in the art work’s title, Tricholoma Equestre. Considered so illustrious that medieval French knights reserved this species for themselves leaving other lowly mushrooms to be eaten by peasants, the sting in the tail is that occasionally the species is poisonous. Privilege has its downfalls.

An elegant and atmospheric small photograph by Layla Rudneva-MacKay hovers fitfully at the edges of visibility and intelligibility. For Layla, the eye is not satisfied with seeing, her practice embodies the desire for knowledge and expression deeper than appearances. Created from numerous pieces of paper then painted with watercolour and arranged to look like a landscape, the artist then photographed the composition in soft focus, hiding any hard edges. Suggestive of natural forms, what might read as a lake, mountain range, and clouds are nonetheless constructs of the imagination projected on to paper, paint, and film. An early art work from a practice that has practice has oscillated through mediums and approaches, Rudneva-MacKay’s photograph remembers a poignant and emotive place that never truly existed, a photograph that examines our relationship with the landscape around us rather than the land itself.

Petra Cortright is an artist who never touches paint or holds a brush. Using a computer and mouse she combs the internet for source material, appropriating websites for images, shapes, colour, and pattern before drawing them into Photoshop. Stripped from their original context, Cortright uses painting software to digitally manipulate her finds, modifying and recombining elements into a digital ‘paint’. The result is classically beautiful compositions that are dense, whimsical, and suggestive of form. Cortright’s practice shifts our understanding of painting, exploring the unfolding relationship between art and technology and the slippery nature of perception. In her hands, painting’s definition becomes intriguingly unstable.

Jessica Winchcombe draws on her own painted canvases as landscapes of sorts, the colours based on different sites or experiences of environment. Winchcombe creates large vividly coloured paintings then shreds them, weaving and plaiting the strips of canvas into densely folded forms presented inside a box frame. In a place of constant geological shift and tectonic movement, her approach recalls recent images post-earthquake (and other natural disasters) or Colin McCahon’s depictions of curved and folded landscapes. Although the canvas is already worked and each strip thoughtfully selected and intentionally woven in particular order, to some degree each of Winchcombe’s art works embrace an uncontrollable meld of shapes and colour. Composition, normally so carefully considered to give a painting it’s emotional charge, is offered up to chance.