Fiona Pardington | Te taha o te rangi

01.05 - 01.06

In 2019 renowned photographer Dr Fiona Pardington relocated to South Canterbury after 25 years in Auckland. In part this was in pursuit of a quieter lifestyle, but also a desire to reconnect with the South Island Te Waipounamu and be closer to her Kāi Tahu, Kāti Mamoe and Ngāti Kahungunu tūrangawaewae and whakapapa.

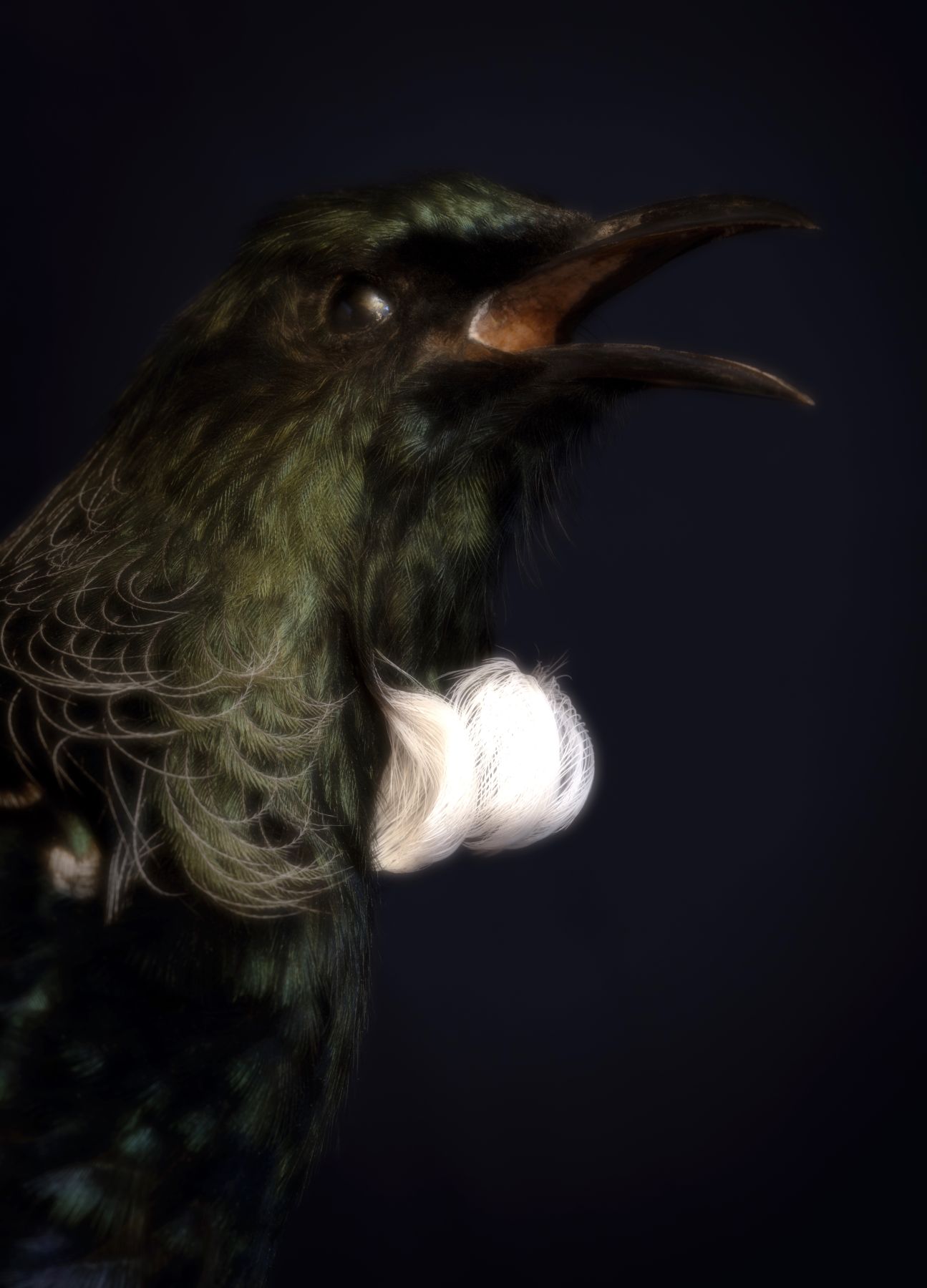

On a chance visit to the South Canterbury Museum in the port town of Timaru in 2023, Pardington was immediately enraptured by the museum’s collection of taxidermy native birds. The taxidermy collection comes from a variety of sources, some amateur, some professional, but most of an exceptional quality that grants the birds an expressive, but naturalistic, charisma. This led Pardington to adopt a new direction in her more familiar approach to her bird photography by focussing on the head as with human portraiture.

This was an opportunity for Pardington to engage more closely with locality and the fabric of her new community. Up among the Hunter Hills, her eyrie where the giant pouākai eagle used to hunt, must, at times, feel near the limits of earth and sky.

The title Te taha o te rangi translates as “the edge of the heavens”. There is a direct connection to be made with the sky, the realm of birds, but in particular the horizon, which alludes to both the seaward views around Timaru, the range of oceanic birds, and the elusive allure of the infinite.

“The edge,” says Pardington, “rather than the centre appeals to me. The edge is still the centre and it unwinds forever, which ever distance covered or turn taken. East to west, north to south, the horizon is inexhaustible, unknown, and unreachable. Much like a rainbow, you chase it but will never catch it.”

The edge of the heavens, the limits of the sky, is the home of the birds, but also the dwelling place of Kahukura and Tūāwhiorangi, the inner and outer components of the double rainbow. According to the “Haka of Raumati”, it is also the dwelling place of Tānerore, the shimmering of heated air, the son of son of Tama-nui-te-rā, the sun, and Hine-raumati, the Summer Maiden. Tānerore is credited with the origin of haka, the dancing air resembling quivering of the hands in haka and waiata. Naturally such images appeal to Pardington – a photographer that paints with light.

Birds have long played an important role in Pardington’s photography. They take many roles in her work. For Māori birds could be a vital source of food and material for kahu huruhuru (feather cloaks), but they could also be messengers of the spirit world, communicating between atua and the mortal world. In Pardington’s work they can symbolise familial love, romantic attachment, ecological warnings, intimations of mortality, or symbols of individual people in her life.

Taxidermy is a strange thing, somewhere between love and death and fetish. Pardington recognised the appeal of the artifice of the way the birds at South Canterbury Museum are posed, the care with which they have been put together, and sometimes their being somewhat worse for wear, while avoiding cutesy anthropomorphism that might otherwise ruin the liminal ambiguity between nature and aesthetic. There is a kind of romantic melancholy to them, a warning – memento mori. Her photographs give them a second life, or perhaps an afterlife, that frees them from the constraints of being a passive object to stare at.

But ultimately this is Birdland, they were here first, where the sky meets the sea, an avian archipelago at the edge of the sky. The edge is an attractive prospect when the centre cannot hold, the falcon cannot hear the falconer and mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.

Fiona would like to acknowledge the support of the South Canterbury Museum is realising this project.

The exhibition will presented in both our Auckland and Queenstown galleries.